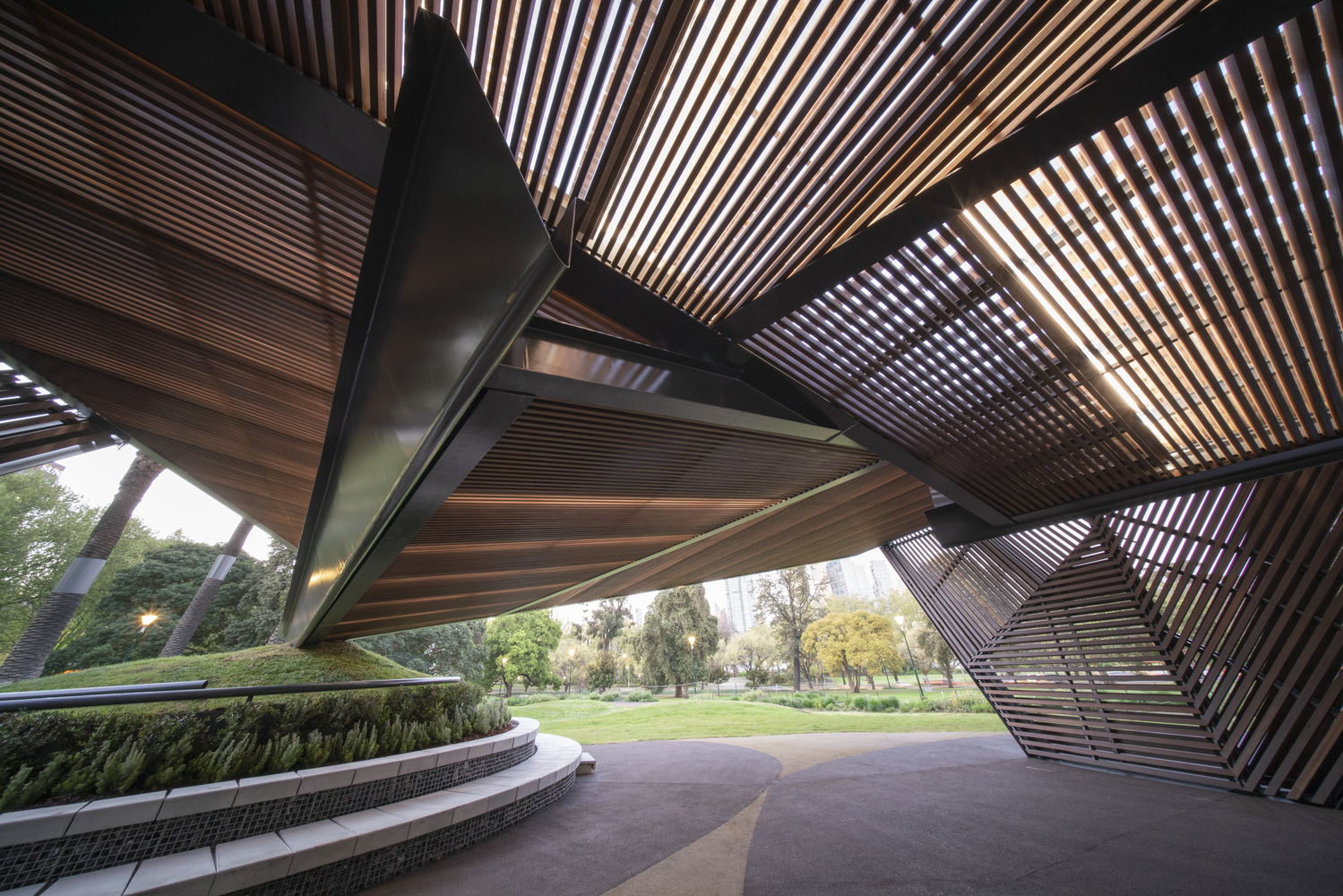

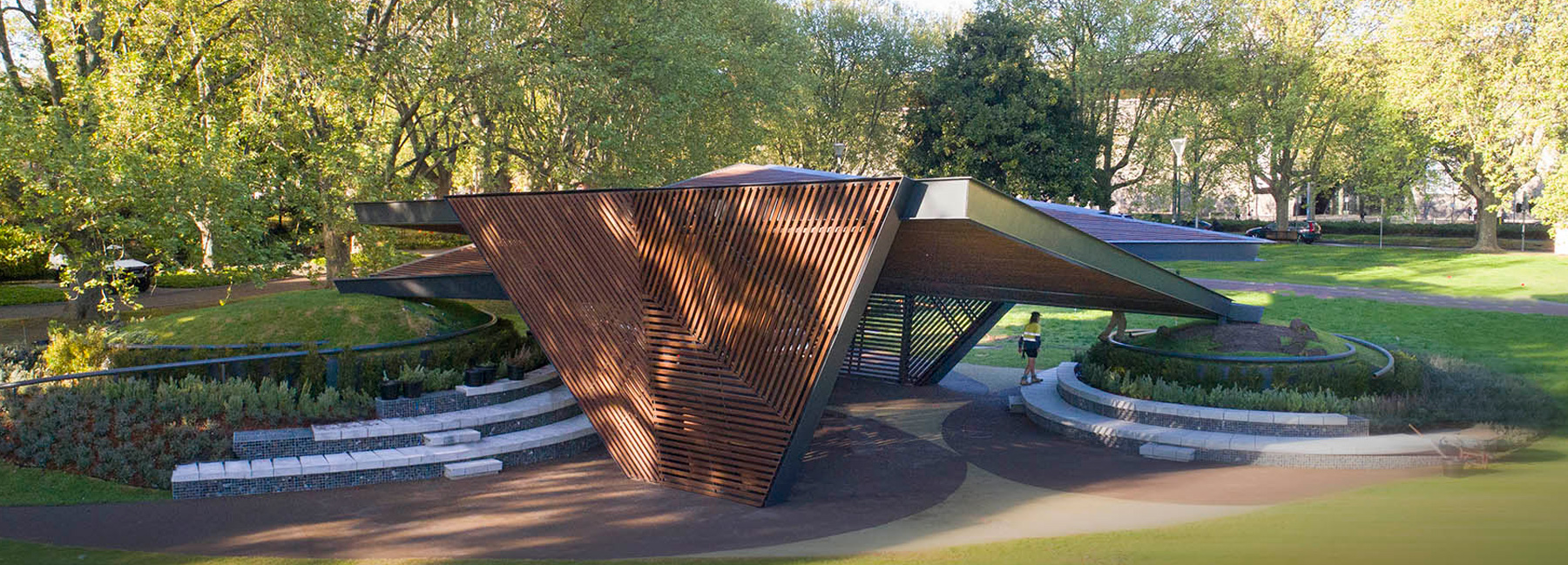

Barcelona, Spain–based architecture firm, Estudio Carme Pinós has designed an intersecting, timber-lattice structure for the fifth-annual MPavilion in Melbourne, Australia. Initiated and commissioned by charity organisation The Naomi Milgrom Foundation, this year’s structure will remain in the city’s Queen Victoria Gardens until February 3, 2019.

The temporary structure is defined by a sharp form, incorporating “floating planes resting at angles on elevated points within the park, connecting the MPavilion to the city.” The design is composed of two distinct halves supported by a central steel portal frame. Two timber latticework surfaces bend and intersect to form a roof, while alterations to the topography form three mounds to create seating.

The sculptural form resembles origami and leads the eye out to the city and back to the pavilion with an aim to dissolve the lines between architecture and urbanism. It establishes a relationship with nature and the surrounding park, where one feels the sun’s path through the game of shadows created by the pavilion’s skin, and where on rainy days the water runs through its transparent roofing.

“In designing this year’s MPavilion, I wanted firstly to make a space for the people of Melbourne to feel connected to each other, to the city they live in, and to nature. We are all part of the world, and architecture can tell that story and provide a place for us to experience life together,” explained Carme Pinós, architect and principle at Estudio Carme Pinós.

MPavilion is designed as both a temporary summer pavilion and ‘an enduring architectural creation’ — and celebrates building communities and social experiences by hosting a series of free talks, workshops, performances and installations. At the end of its four-month tenure, it is gifted to the city and moved to a permanent new home to be engaged by the community in perpetuity, creating an ongoing legacy.

“MPavilion 2018 is a place for people to experience with all their senses, to establish a relationship with nature, but also a space for social activities and connections,” said Pinós. “Whenever I can, I design places where movements and routes intersect and exchange, spaces where people identify as part of a community, but also feel they belong to universality.”

“Working with Carme to bring her inspiring MPavilion design to life has been an absolute pleasure,” said Naomi Milgrom, chair of the Naomi Milgrom Foundation. “Carme’s vision opens Australia to conversation about how to make our cities more inclusive through design. It’s a privilege to commission a work with such international and future thinking insight.”

Images: John Gollings

Living within a consumer society means that retail is dramatically growing.

In fact, retail covers 43% of the total value of commercial property, and a House of Commons report states that during 2014, consumers in the UK spent around a staggering £378 billion.

Today we spend more and more time in retail centres indulging in our passion for “consumerism” or “retail therapy,” hence consumer brands are looking to different ways to create more restorative, positive shopping experiences.

As it turns out, the benefits of biophilia in retail spaces are well established.

In 2016, The World Green Business Council report demonstrated that biophilic design optimises retail environments.

Because the concept connects humans to natures, in some ways, its approach to design takes the idea of sustainability to a new level.

The positive effects of daylight and greenery on consumers and staff can further be amplified by including other biophilic elements like natural wood, which has been shown to reduce stress and increase social interactions.

Wood not only improve aesthetics, but add comfort and sophistication, and all the other benefits that biophilic design brings.

By embracing the use of multiple biophilic elements; natural lighting, wood, greenery and water features, customers will feel more empowered to relax, take their time, and shop around.

These natural elements shape our everyday environment, and foster a sense of warmth, calmness and comfort.

A study entitled “Negative affect: The Dark Side of Retailing” reveals that approximately 10% of shoppers enter a store in a negative mood; which makes the act of shopping a stressful and potentially irritating one.

This can impact overall consumer spend and centre profitability.

However, by consciously altering the store atmosphere through spacial layout, lighting, temperature, product placement and integrating greenery can greatly enhance positive consumer experience.

According to a report on The Economics of Biophilia;

- The restorative and calming effect of nature helps draw shoppers into stores and creates positive emotions towards making a purchase

- Shoppers’ perceptions of the value and quality of good increases in line with the amount of greenery and vegetation within the space

- Shoppers are more likely to dwell longer within the store

- Shoppers are more likely to accept higher prices

- Store lit by daylight can see significant sales boosts of 15 – 20%

In applying the idea of biophilic design to the retail environment, the idea is centred on the inherent connection to nature in order to create spaces that are stress-free and that encourage successful shopping experiences both for the consumer and retailer.

Simply introducing greenery, especially in vertical wall applications, creates a sense of freshness and offers aesthetic appeal, filters the air and improves the acoustics within a space, which in turn reduces customer stress, irritability, and visual fatigue and increases their dwell time.

“A new breed of businesses is emerging which understands that better shopping environments lead to better experiences for consumers, which, in turn, lead to better economics for retailers,” says Terri Wills, CEO of the World Green Business Council.

Indoor plants are, of course, not the only natural elements that can be incorporated into a space; they are, however, as close as one is likely to get to nature in most indoor settings.

Natural light is an instant mood enhancer and creates an energising yet calming and inviting atmosphere.

A space that receives sufficient natural light instantly appeals to customers and increases their dwell time spent in the store.

A study conducted in a chain of 70 retail stores across California — 49 of which relied on artificial lighting, links daylight to retail sales.

The report makes it clear that there was a 40% increase in sales after the installation of skylights within these stores.

The retail store business model across Europe is also starting to capitalise on daylighting to not only increase profits but also improve customer mood.

One of the most powerful effects of daylight is its psychological effects on retail staff: improving their motivation, productivity and overall job satisfaction.

In addition, it improves the company’s’ store economically, by helping to reduce its heating and cooling costs.

Published to coincide with the review of the Letwin Review of House-building, the RIBA’s “Ten Characteristics of Places Where People Want to Live” highlights a series of case studies that demonstrate components of contemporary community housing design.

The study, with input from RIBA Planning Group, identifies and analyses specific, successful elements of past projects and offers an insight into what makes great places — and what can be easily incorporated into future projects in England and the world at large.

The study provides valuable evidence demonstrating to its readers the relationship between design quality and the rate of supply in the delivery of much needed affordable housing.

Each building highlighted illustrates how appealing successful new housing looks and feels — and how each design can be easily replicated across the country.

“The necessary context for successful place-making is often neglected, but only by addressing this can we improve both the quality of the homes we are building and the rate of supply. High-quality design is essential, but it must be founded upon the right leadership, the right funding and delivery” Ben Derbyshire, RIBA President

1. The right place for the right housing

Location plays a primary influence in the choice of a new-building home.

Visually attractive settings are a favoured option, particularly when supported by essential local services: schools, healthcare, green open space, as well as access to retail and employment opportunities.

Having physical connectivity to the surrounding context makes a successful place-making.

2. A place to start and a place to stay

A successful housing project should incorporate a mix of uses, for young renters and flat-sharers, families as well as empty nesters and older people — resulting in a broadened market demand.

Offering spontaneous local activities and places to shop, socialise and relax further promotes community inclusion, cohesion and resilience — while encouraging people to stay in the community throughout different phases of their lives.

3. A place that fosters a sense of belonging

How we relate to design can evoke an emotional response; similarly, neighbourhoods create a strong visual identity that stems from its immediate environmental, social and historical context.

The inherent quality of buildings and landscape character lends an “authentic and unique sense of place,” ensuring that the area matures and improves over time.

4. A place to live in nature

Nature has benefits for the body and mind and makes up an essential part of a new neighbourhood.

Open green spaces and biodiversity create a high quality and visually rich environment that matures over time.

Parks, village greens, gardens squares and shared gardens not only shapes the character of a place but encourages community interaction and active outdoor living.

5. A place to enjoy and be proud of

To foster identity one has to be part of something, and that’s true with neighbourhoods.

Places with authentic, tangible character and distinctive streetscapes are noted as “appealing to a wider range of potential homeowners and residents.”

Design that provides engaging views, vistas and skylines captures attention and easily becomes a place that residents enjoy and are proud of.

6. A place with a choice in homes

Modern buyers and renters aspire to a choice of house types and buildings that offer flexibility throughout their lifetime.

Homes can be designed to be more generally adaptable but also accommodate individuals’ changing needs.

The report highlights that “empowering communities to participate in the process of designing and building out their own homes has the potential to produce higher quality housing that responds to local needs and therefore increases build-out rates.”

7. A place with a unique and lasting appeal

Having a choice of authentic and high-quality homes is more desirable and crucial in creating a place people wish to live.

“Inherently authentic, memorable and delightful, new housing has a locally-rooted character drawn from its surroundings, but also a strong identity of its own,” notes the report.

8. A place where people feel at home

Everyone has an idea of what “home” means to them, the study however suggests that “good proportion, imaginative details, warm materials, and a sense of enclosure, seclusion and space” are essential.

Self-finishing can be handled by occupants in order to draw more deeply on what home means to an individual while maintaining the controlled variety of the streetscape.

9. A sustainable place for future generations

It’s worth noting that, “homes in healthy, clean, resource-efficient neighbourhoods in the right places are more likely to attract potential owners or tenants by costing less to run from the start and retaining inherent value in the long term.”

Innovative parking strategies, future reduction in car-use, reducing carbon footprint as well as minimising energy loss helps us look towards a sustainable future.

10. A place where people thrive

Good spacial design attract potential homeowners and renters and positively impact how we live.

Creating interiors that are spacious, well laid-out, good indoor air quality and daylight benefits inhabitants both physically and mentally — while inherently energy-efficient homes are more affordable to maintain.

A 2017 study in the Journal of Mechanical Design revealed that people were more willing to buy “green” if a product highlighted sustainable features, which appealed to consumers’ environmental consciousness.

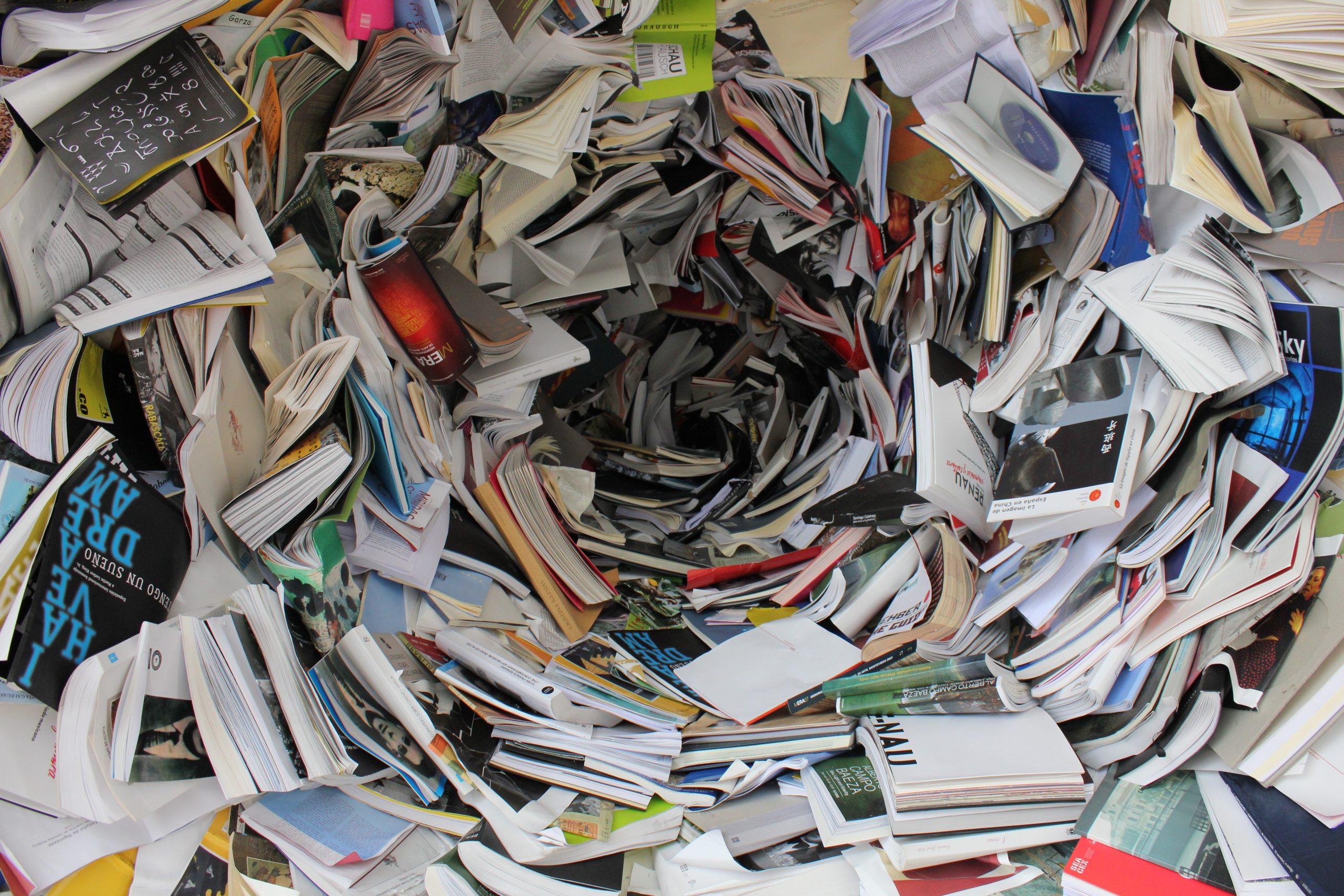

Over the past few years, environmental concerns have become more important and the demand for recycled products has been growing significantly, leading many companies to design products around sustainability principles.

More and more companies are increasingly “thinking green” and how to reduce consumer waste.

This is partly due to companies and consumers becoming more aware of the importance to protect the environment.

With innovative recycling initiatives and programs aimed at making the world — and the environment — a better place; retailers and consumer brands are curating spaces and developing products that offer “live” recycling over the course of the purchase period.

These products and experiences offer consumers the opportunity to engage in consumption habits that lessen their ecological footprints, encouraging more interaction and less semonising around the subject of environmental change and betterment.

Consumers are more informed now, which allows them to walk into commercial transactions armed with in-depth understanding about any particular brand or product.

Being a sustainable company is more than just doing the right thing, it can be beneficial for businesses as consumers are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products.

A study by Sloan Management Review reveals that the extent to which a consumer brand incorporates sustainability as part of its business model often correlates to increase in profit — especially if the recycled product works just as well as the traditional product.

A study by Nielsen found that 55% of consumers are willing to pay more for products and services provided by companies that are committed to a positive social and environmental impact.

“Consumers around the worlds are saying loud and clear that a brands’ social purpose is among the factors that influence purchasing decisions” said Amy Fenton, global leader of public development and sustainability, Nielson.

The same study highlighted that millennials (age 21-34) represent 51% of respondents who are willing to pay extra for recycled products.

And that millennials are three times more agreeable to sustainable actions than generation X (35-49) and twelve times more than baby boomers (age 50-64).

The data further goes to show that if a company didn’t address sustainability they’d be out of business within 10 years.

Other companies can therefore draw inspiration from brands that are incorporating real-time recycling initiatives and using “environmentally friendly” as a component of their value proposition.

For example, European furniture company Pentatonic, manufactures its furniture from post-consumer trash — an unending incentivised furniture recycling program that aims to “radically transform consumption culture”.

It recycles its own products into new products once the piece has outlived its use, bringing the consumer into the product supply chain.

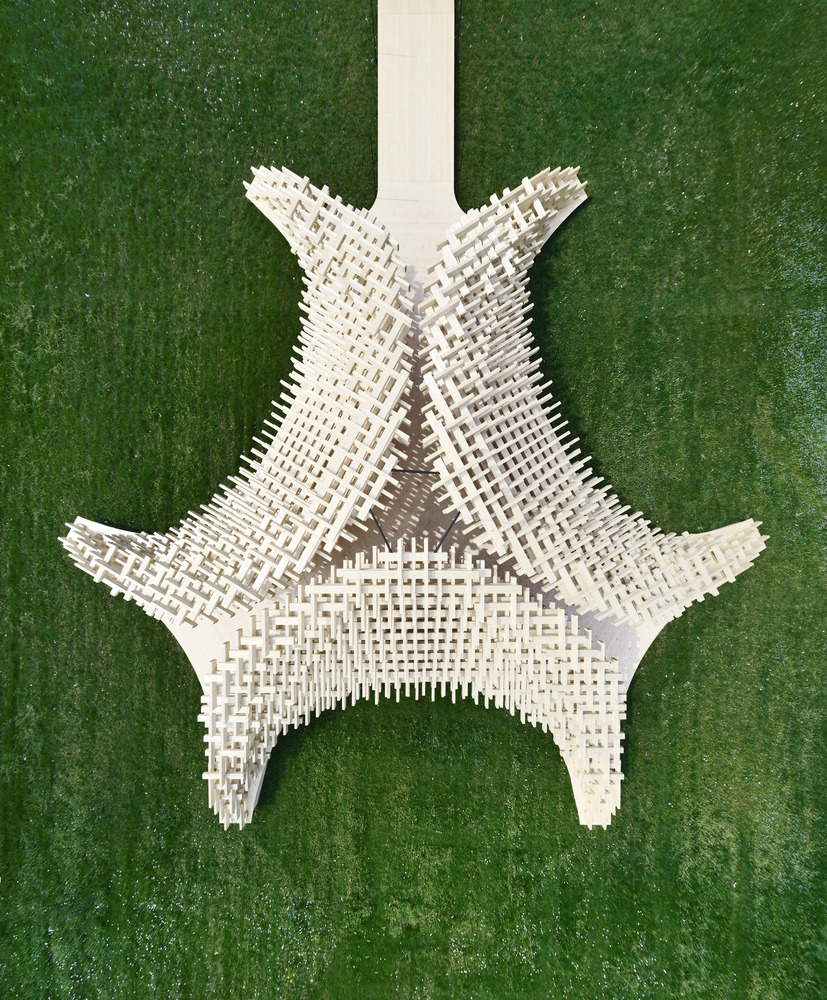

Peter Pichler Architecture, a Milano-based firm has built a temporary structure as part of Milan Design Week 2018.

Referred to as “Future Space,” the symmetrical structure is installed in the courtyard of Ca’ Granda, a Renaissance-inspired complex belonging to the University of Milan.

The project, headed by Italian architect Peter Pichler, features over 1,600 wooden beams stacked on top of another to form an intricate pavilion, with an overall weight of 12 tons.

The giant wooden sculpture plays with the fundamental elements of Renaissance style: symmetry, proportion and geometry — and acts as a cave, allowing visitors the freedom to enter in by evoking a playful game of light and shadow.

Pavilion Salone del Mobile reflects on how wood can be used to create a spatial experience akin to Renaissance architectural influences.

“The project explores the potential of the matric presence of wood in a non-typical “building” environment as a structure that should transmit a spatial experience,” said Pichler.

The pavilion is formed by three separate wings, arranged together to create a pyramid-like enclosure.

The beams vary in height by simply stacking and rotating different lengths, which give the structure its curving geometric.

“Visitors are invited to enter and explore the cave-like installation,” said Pichler. “The perforated structure filters light and evokes a playful game of light and shadow,” he continued. “It forms three openings — one serves as the entrance and the other two provide views towards the courtyard of the university and other installations.”

The architect believes his design embraces his studios’ believe that wood will be the building material of the future.

“We think that, in the future, wood will more and more play an important role in architecture,” said Pichler.

“I think our installation reflects the way we work and what is important to us: beauty, sustainability, the impact of light and shadow, and the spatial experience,” he added.

Images: Oskar Dariz (http://www.dariz.com/)

Canadian architect Asher deGroot of MOTIV Architects designed a modern barn in rural Langley, BC, Canada, known affectionately as Swallowfield for his parents Dennis and Jenny deGroot, who own the farm.

The simplicity of the design is intentionally reminiscent of traditional North American barns, clad in vertical Douglas fir sliding, reclaimed from prior use as board-form concrete formwork; which allowed the project to be constructed on a modest budget.

The reclaimed timber has visible marks and stains of the boards’ previous life, maintaining the patina and memory as the material ages and weathers.

To construct Swallowfield Barn, the architect acted as the builder for the project; and along with his father, they coordinated specific build days with a crew of up to 40 people.

“The goal of the project was to build a new barn and gathering space in the manner of traditional barn-raisings, using simple techniques and readily available materials,” said the architect.

The project had two main objectives — to design for simple inhabitants; resident cattle, sheep, swine, cats, as well as workshops and storage.

The second objective was to conceive a spacious hayloft that can function as a vibrant community gathering space, suitable for hosting concerts, weddings, art shows, poetry readings, fundraisers and long-table dinners.

The frames of the roof structure were constructed completely on site and raised into place in less than four hours.

The barns’ eye-catching and distinct off-kilter pitched roof creates a warm and inviting entrance — designed in collaboration with timber engineer Eric Karsh.

Inside, the barn’s “cathedral-like design” highlights the potential for engineered wood flooring to be celebrated in an exposed application and elevates the material to new heights, expressing the beauty of its strength and simplicity.

The ground floor is spacious, with multiple entryways and alleys designed for moving farming equipment and animals.

Large sliding doors create a generous indoor-outdoor work area- protected by the roof overhang above.

The repetitive roof structure upstairs draws the eye upward to the long linear skylight at the ridge.

The barn requires no daytime lighting and is naturally heated during the shoulder seasons.

Images: Ema Peter (http://www.emapeter.com/)

The prevailing approach to the design of cities has been built in ways that it excludes the human from the natural world. Biophilic design is an innovative way of designing health and productivity habitats; places where we live, work and learn.

First popularised by biologist and author Edward Wilson — the principle of biophilic proved instrumental in enhancing human physical, emotional and intellectual fitness during the long course of human evolution.

Research scientists and design practitioners have been working for decades to define aspects of nature and our need for it in a deep and fundamental fashion, in ways that it impacts human health, productivity, well-being and our satisfaction with the built environment.

Simply put, biophilic is the humankind’s innate biological connection with nature.

It takes us on a journey and explains why a garden view can enhance our creativity; strolling through a park has restorative, healing effects; why patients heal faster when in contact with nature and why some workers are more productive than others.

As the world population continues to urbanise, biophilic design qualities are even more important.

How do we then design environments that have biophilic attributes and effectively enhance health and well-being?

It involves the application of diverse design strategies, and this includes three ways of experiencing nature in the built environment:

the direct experience of nature (light, air, water, plants, natural landscapes), the indirect experience of nature (images of nature, natural materials, natural colours), and the experience of space and place (transitional spaces).

The successful application of biophilic design requires consistently adhering to a number of basic objectives or principles. They include:

- Biophilic design emphasizes human adaptations to the natural world that over evolutionary time have proven instrumental in advancing people’s health, fitness, and wellbeing. Exposures to nature irrelevant to human productivity and survival exert little impact on human well-being and are not effective instances of biophilic design.

- Biophilic design depends on repeated and sustained engagement with nature. An occasional, transient, or isolated experience of nature exerts only superficial and fleeting effects on people, and can even, at times, be at variance with fostering beneficial outcomes.

- Biophilic design requires reinforcing and integrating design interventions that connect with the overall setting or space. The optimal functioning of all organisms depends on immersion within habitats where the various elements comprise a complementary, reinforcing, and interconnected whole. Exposures to nature within a disconnected space; such as an isolated plant or an out of context picture or a natural material at variance with other dominant spatial features — is NOT effective biophilic design.

- Biophilic design fosters emotional attachments to settings and places. By satisfying our inherent inclination to affiliate with nature, biophilic design engenders an emotional attachment to particular spaces and places. These emotional attachments motivate people’s performance and productivity and prompt us to identify with and sustain the places we inhabit.

- Biophilic design fosters positive and sustained interactions and relationships among people and the natural environment. Humans are a deeply social species whose security and productivity depends on positive interactions within a spatial context. Effective biophilic design fosters connections between people and their environment, enhancing feelings of relationship, and a sense of membership in a meaningful community.

It is fundamental for architects and designers to understand the projects’ design intention and understand the health and performance priorities of the intended users.

To identify and take into account the design strategies that restores and enhances the users’ well-being and interaction with the building.

The 16th edition of Frieze London opened its marquees to collectors and curators in London’s gracious and spacious Regent’s Park.

The contemporary art fair, which features more than 160 galleries from around the world, revealed contemporary artworks designed both to challenge and inspire.

Frieze London is broken into different groupings — the Main section, the Focus section, and the new Social Work section.

This year, The London event had a de facto girl power theme.

The Social Work section presented the work of eight pioneering women artists whose work challenged the political status quo and patriarchy in the ’80s and ’90s.

Showcasing artistic works; from Sonia Boyce’s Afro Caribbean inspired canvases to the late Helen Chadwick’s provocative anatomical sculptures.

The Modern Institute presented works by the brilliant Glaswegian artist Cathy Wilkes, who has been chosen to represent the UK at the 2019 Venice Biennale. Galleria Fonti, Naples, Italy | Frieze London, Main

Frieze Focus section dedicated to hot new talent, welcomed 33 galleries this year; from Hong Kong-based Wong Ping’s immersive neon works, to Uriel Orlow Theatrum Botanicum, a giant conceptual herbarium designed to highlight the plant world’s role in our existence.

This year’s Camden Arts Centre Emerging Arts Prize went to Ping, which included receiving a solo show at the Camden Arts Centre England within the next year and a half.

Frieze London has enjoyed long-standing sponsorship from Deutsche Bank Wealth Management; and this year, in collaboration with the bank, provided selected guests with the opportunity to view an exclusive exhibition inside Deutsche Bank’s Wealth Management Lounge.

Curated by leading British artist Tracey Emin, the exhibition titled Another World, presented exclusively female artists from the bank’s collection as a special celebration marking 100 years since British women first had the right to vote.

Images: Frieze London 2017. Photo by Mark Blower, courtesy of Mark Blower/Frieze

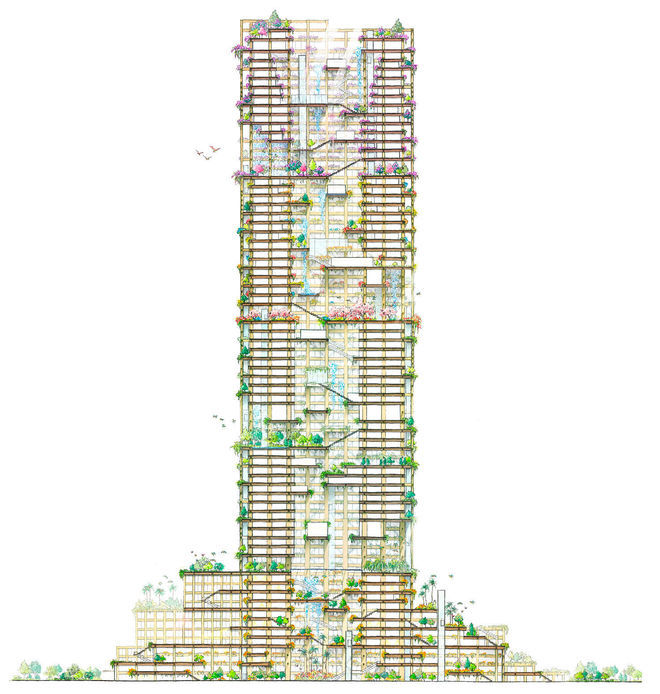

Japanese developer Sumitomo Forestry Co. and architects Nikken Sekkei have unveiled plans for the world’s tallest wooden skyscraper — a 1,148-foot (350m) tower; comprising of stores, offices, hotels and private homes.

Positioned in central Tokyo, the 70-storey building will be a hybrid of mostly wood and steel capable of handling Tokyo’s high seismic activity (with wood accounting for 90 percent of the construction material).

Set out to be both the tallest building in Japan and the tallest wooden structure in the world; construction is aimed for a 2041 completion date to mark Sumitomo’s 350th anniversary.

According to Sumitomo Forestry website, which highlights that “happiness grows from trees,” the ultimate aim of the proposed structure referred to as W350 Project, is to create environmentally-friendly, timber-utilising cities which “become forests through increased use of wooden architecture for high-rise buildings”.

The building is expected to cost about £4.2 billion (600 billion Japanese yen) which is twice the amount of a mainstream skyscraper of the same size.

Sumitomo Forestry, however, believes that due to technological developments, it expects the costs to fall before the completion of the building in 2041.

At every level, the building will heavily feature greenery on balconies, offering “a view of biodiversity in an urban setting”.

The architects’ sketches also reveal broad balconies and water features that continue around all four sides of the building, giving a space “in which people can enjoy fresh outside air, rich natural elements and sunshine filtering through foliage.”

With earthquakes being a concern in Japan, the building will incorporate a structural system composed of braced tubes made from columns, beams and braces that are able to withstand strong winds and the earthquakes.

Images: Sumitomo Forestry Co. (http://sfc.jp/english/)

Command of the Oceans reveals a full dockyard story, thrilling archaeology and long-hidden objects, whilst highlighting compelling stories of innovation and craftsmanship.

First conceived in 1995; with the discovery of an 18th-century naval warship called Namur — beneath several layers of floorboards in one of the dockyard buildings.

Hailed as the most significant naval archaeological discovery since Mary Rose; the project at Chatham Historic Dockyard by London studio Baynes and Mitchell Architects, is a heritage landscape and scheduled ancient monument that highlights the progressive conservation, inventive re-use and adaptation of existing fabric.

The architectural firm was tasked with carrying out an extensive restoration, and asked to create a new building that will be a gateway to spaces that represents the ships’ remains as well as other exhibits

The ancient timber from the Namur became the focal point of Command of the Oceans.

The striking new 6-metre entrance building clad in black zinc, inserted into the long thin gap that knits together adjoining workshops constructed using timber salvaged from warships; which have been renovated and adapted to form exhibition spaces, new galleries and retail spaces.

The entrance building also connects the ground-floor areas to a new sunken gallery space where visitors are given the opportunity to view the collection of the timbers forming ‘the ship beneath the floor’.

“We thought it was important that the visitor be able to inhabit the space the timbers were in,” the studio’s co-founder Alan Mitchell explained. “We needed to provide a way for people to get a sense of the scale of this archaeological find and experience it all at once.”

The idea of using a black galvanized zinc cladding rather than a white structure that would match existing buildings adds a contemporary feature that provides a strong presence within the dockyards complex.

“The two buildings on either side of this gap have a very traditional docklands profile with the saw-tooth roof,” said Mitchell. “The idea was to continue that approach but change the rhythm by introducing a change in height.”

The modest entrance is immediately obvious to visitors as they approach the large car park, which is situated above the old mask pond.

“As people approach the site, often from a distance, the building needs to announce itself in this quite robust context by being bigger and a different colour to the adjacent buildings.”

Internally, the historic buildings feature traditional roof trusses constructed from large structural timbers taken from ships — adding to the beauty of the refurbished spaces.

A palette of material consisting of black metal, black limestone, board-marked concrete and composite timber create a warm and tactile feel throughout the rooms.

Furthermore, the carefully chosen material responds robustly to the strong, industrial language of the existing Historic Dockyard Chatham buildings and landscape.

Images: Hélène Binet (http://www.helenebinet.com/)